Bimatoprost

General Information about Bimatoprost

Additionally, ongoing research has instructed that bimatoprost may have a role in the remedy of hair loss on the scalp, making it a multi-faceted treatment with promising potential. In conclusion, bimatoprost is a extremely versatile drug that has proven to be efficient in the remedy of a spread of eye circumstances and is now also being explored for its beauty and dermatological advantages.

Ocular hypertension, on the other hand, is a situation by which the pressure inside the attention is greater than normal, nevertheless it has not yet caused any injury to the optic nerve. If left untreated, ocular hypertension can result in the development of glaucoma. Bimatoprost is also used for cosmetic functions, because it has been discovered to stimulate the growth of eyelashes. This is a great advantage for these who have thin or sparse eyelashes, as it may possibly provide them with fuller and longer lashes.

The use of bimatoprost for this objective has gained popularity lately and is broadly generally known as a safe and effective method to achieve stunning eyelashes. Apart from these widespread uses, bimatoprost has additionally been studied for its potential benefits in treating varied different eye conditions such as dry eye syndrome and vitreous floaters.

Bimatoprost is a medicine that has been broadly used in the remedy of various eye conditions corresponding to glaucoma, ocular hypertension, and lengthening eyelashes. It belongs to a category of drugs known as prostaglandin analogues and works by reducing stress within the eye through increased drainage of fluid. This helps in stopping harm to the optic nerve and consequent vision loss, which is the hallmark of glaucoma.

Lead acetate (sugar of lead) has been used in therapeutics 5 medications that affect heart rate cheap bimatoprost 3 ml fast delivery,* lead carbonate (white lead) is still used in paints, lead oxide (litharge) is essential for glazing of pottery and enamel ware, and tetraethyl lead is mixed with petrol as an antiknock to prevent detonation in internal combustion engines. Summary of some of the common non-occupational sources: Candle with lead-containing wicks Ayurvedic medicines Paint Retained bullets Ink Automobile storage battery casing; battery repair shops Ceramic glazes Lead pipes Silver jewellery workers Renovation/modernisation of old homes. Children, however, absorb approximately 50% of ingested lead and retain about 30%. Usual Fatal Dose this is not really relevant to lead since acute poisoning is very rare. The average lethal dose is said to be 10 gm/70 kg for most lead salts, while it is 100 mg/kg for tetraethyl lead. Occupational exposure results mainly from inhalation, while in most other situations the mode of intake is ingestion. In children about 70% of total body lead is skeletal, while in adults over 95% is in osseous tissues. These include the radius, tibia, and femur, which are the most metabolically active. Y Significant amounts of skeletal lead are released from bone into the blood stream periodically resulting in symptoms of toxicity. The conditions favouring this include acidosis, fevers, alcoholic intake, and even exposure to sunlight. Absorbed lead which is not retained in the body is excreted primarily in the urine (about 65%) and bile (about 35%). It decreases haeme synthesis by inactivating the enzymes involved such as aminolaevulinic acid dehydrase, aminolaevulinic acid synthetase, coproporphyrinogen oxidase (or decarboxylase), and ferrochelatase. The highest brain concentrations of lead are found in hippocampus, cerebellum, cerebral cortex, and medulla. Interstitial nephritis, reduced glomerular filtration rate, and nonspecific proximal tubular dysfunction are typical. In addition, lead can decrease uric acid renal excretion, thereby raising blood urate levels and predisposing to gout (saturnine gout). Elevated urinary levels of N-acetyl-3-D-glucosaminidase and beta-2-microglobulin may serve as early markers of renal injury. Lead appears as a trace metal in virtually all foods and beverages, though fortunately absorption from such sources is relatively low. Adults ingest 300 mcg and inhale 15 mcg of lead approximately each day, of which only 10% is absorbed, but children may absorb upto 50%. An important source of food based lead poisoning is the use of lead-soldered canned food and drink. The concentration of lead which may not really be very high in ground or surface water may progressively rise as it passes through the distribution system because of contact with lead connectors, lead service lines or pipes, lead soldered joints, lead containing coolers, and lead impregnated fixtures such as brass taps. Because of the reasons mentioned, minute quantities of lead are always present in the blood of even normal individuals. Only when the concentration is high, do features of intoxication begin to manifest. However there are reports that adverse effects especially on the haematopoietic system can occur at levels as low as 10 mcg/100 ml. Hence, the current trend is to consider even levels as low as 10 mcg/100 ml as unacceptable, especially in children. Many reported cases of acute poisoning may actually be exacerbations of chronic lead poisoning when significant quantities of lead are suddenly released into the bloodstream from bone. Symptoms include metallic taste, abdominal pain, constipation or diarrhoea (stools may be blackish due to lead sulfide), vomiting, hyperactivity or lethargy, ataxia, behavioural changes, convulsions, and coma. There is sudden onset of vomiting, irritability, headache, ataxia, vertigo, convulsions, psychotic manifestations, coma, and death. Even if recovery occurs, there is often permanent brain damage manifesting as mental retardation, cerebral palsy, optic neuropathy, hyperkinesis, and periodic convulsions. Note: Facial pallor, especially circumoral is said to be a characteristic feature of chronic lead poisoning and is due to vasospasm, though anaemia may contribute to a significant extent. The anaemia that is encountered in plumbism is similar to that due to iron deficiency, i. Increasing blood lead levels in children have been correlated with hearing impairment, developmental delay, aggressive, hyperactive and antisocial behaviour, visual problems, and growth retardation. It can affect reproduction in males and females, and affects neurodevelopmental milestones in children with both prenatal and postnatal exposure. Lead poisoning during pregnancy has been associated with prematurity, low birth weight, and impaired foetal growth. The current paediatric practice in the West is to first measure the free erythrocyte protoporphyrin before carrying out a blood lead quantification. A similar dark line is sometimes seen in poisoning due to mercury, iron, thallium, silver, or bismuth as one of the earliest and most reliable indicators of the impairment of haeme biosynthesis. But ZnP can be elevated in iron deficiency anaemia while the blood lead level is actually within normal limits. Hence when ZnP is raised, it is mandatory to confirm lead poisoning by performing a blood assay for lead level. Blood Complete blood count and peripheral smear- General and non-specific findings include low haematocrit and haemoglobin values with normal total and differential cell counts. Basophilic stippling is usually seen only in patients who have been significantly poisoned for a prolonged period.

The virus has been detected in the Torres Strait islands symptoms joint pain order discount bimatoprost line, and a human encephalitis case has been identified on the nearby Australian mainland. This flavivirus is particularly common in areas where irrigated rice fields attract the natural avian vertebrate hosts and provide abundant breeding sites for mosquitoes such as C. An effective, formalin-inactivated vaccine purified from mouse brain is produced in Japan and licensed for human use in the United States. It is given on days 0, 7, and 30 or-with some sacrifice in serum neutralizing titer-on days 0, 7, and 14. Vaccination is indicated for summer travelers to rural Asia, where the risk of clinical disease may be 0. The severe and often fatal disease reported in expatriates must be balanced against the 0. These reactions are rarely fatal but may be severe and have been known to begin 19 days after vaccination, with associated pruritus, urticaria, and angioedema. Live attenuated vaccines are being used in China but are not recommended in the United States at this time. The febrile-myalgic syndrome caused by West Nile virus differs from many others by the frequent appearance of a maculopapular rash concentrated on the trunk and lymphadenopathy. Headache, ocular pain, sore throat, nausea and vomiting, and arthralgia (but not arthritis) are common accompaniments. West Nile virus was introduced into New York City in 1999 and subsequently spread to other areas of the northeastern United States, causing >60 cases of aseptic meningitis or encephalitis among humans as well as dieoffs among crows, exotic zoo birds, and other birds. The virus has continued to spread and is now found in almost all states, Canada, and Mexico. Annually, 10003000 cases of encephalitis with 100300 deaths are reported in the United States. In addition to the more severe motor and cognitive sequelae, milder findings may include tremor, slight abnormalities in motor skills, and loss of executive functions. Intense clinical interest and the availability of laboratory diagnostic methods have made it possible to define a number of unusual clinical features, including chorioretinitis, flaccid paralysis with histologic lesions resembling poliomyelitis, and initial presentation with fever and focal neurologic deficits in the absence of diffuse encephalitis. Virus transmission through both transplantation and blood transfusion has necessitated screening of blood and organ donors by nucleic acidbased tests. The latter two viruses are both maintained in mosquitoes and birds and produce a clinical picture resembling that of Japanese encephalitis. Murray Valley virus has caused occasional epidemics and sporadic cases in Australia. Rocio virus caused recurrent epidemics in a focal area of Brazil in 19751977 and then virtually disappeared. From Scandinavia to the Urals, central European tick-borne encephalitis is transmitted by Ixodes ricinus. A related and more virulent virus is that of Russian spring-summer encephalitis, which is associated with I. The ticks transmit the disease primarily in the spring and early summer, with a lower rate of transmission later in summer. The risk varies by geographic area and can be highly localized within a given area; human cases usually follow outdoor activities or consumption of raw milk from infected goats or other infected animals. After an incubation period of 714 days or perhaps longer, the central European viruses classically result in a febrile-myalgic phase that lasts for 24 days and is thought to correlate with viremia. A subsequent remission for several days is followed by the recurrence of fever and the onset of meningeal signs. Spinal and medullary involvement can lead to typical limb-girdle paralysis and to respiratory paralysis. The encephalitic syndrome caused by these viruses sometimes begins without a remission and has more severe manifestations than the European syndrome. Mortality is high, and major sequelae-most notably, lower motor neuron paralyses of the proximal muscles of the extremities, trunk, and neck-are common. Thrombocytopenia sometimes develops during the initial febrile illness, which resembles the early hemorrhagic phase of some other tick-borne flaviviral infections, such as Kyasanur Forest disease. Other tick-borne flaviviruses are less common causes of encephalitis, including louping ill virus in the United Kingdom and Powassan virus. However, effective alum-adjuvanted, formalininactivated vaccines are produced in Austria, Germany, and Russia. Since rare cases of postvaccination Guillain-Barré syndrome have been reported, vaccination should be reserved for persons likely to experience rural exposure in an endemic area during the season of transmission. Cross-neutralization for the central European and Far Eastern strains has been established, but there are no published field studies on cross-protection of formalin-inactivated vaccines. Prompt administration of high-titered specific preparations should probably be undertaken, although no controlled data are available to prove the efficacy of this measure. Immunoglobulin should not be administered late because of the risk of antibody-mediated enhancement. Other ticks may transmit the virus in a wider geographic area, and there is some concern that I. Patients with Powassan encephalitis (many of whom are children) present in May through December after outdoor exposure and an incubation period thought to be 1 week. Human cases present from June through October, when the birdCuliseta mosquito cycle spills over into other mosquito species such as A.

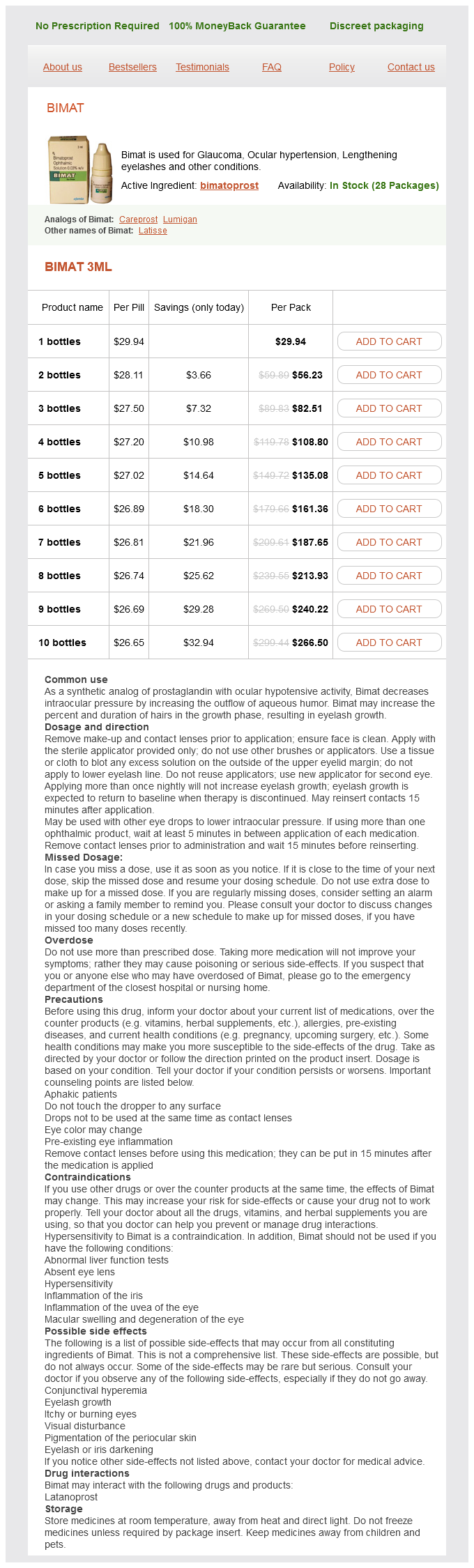

Bimatoprost Dosage and Price

Bimat 3ml

- 1 bottles - $29.94

- 2 bottles - $56.23

- 3 bottles - $82.51

- 4 bottles - $108.80

- 5 bottles - $135.08

- 6 bottles - $161.36

- 7 bottles - $187.65

- 8 bottles - $213.93

- 9 bottles - $240.22

- 10 bottles - $266.50

Many clinical abnormalities have been described in acute malaria symptoms zinc poisoning 3 ml bimatoprost order mastercard, but most patients with uncomplicated infections have few abnormal physical findings other than fever, malaise, mild anemia, and (in some cases) a palpable spleen. Anemia is common among young children living in areas with stable transmission, particularly where resistance has compromised the efficacy of antimalarial drugs. Mild jaundice is common among adults; it may develop in patients with otherwise uncomplicated falciparum malaria and usually resolves over 13 weeks. Malaria is not associated with a rash like those seen in meningococcal septicemia, typhus, enteric fever, viral exanthems, and drug reactions. Petechial hemorrhages in the skin or mucous membranes-features of viral hemorrhagic fevers and leptospirosis-develop only rarely in severe falciparum malaria. However, once vital-organ dysfunction occurs or the total proportion of erythrocytes infected increases to >2% (a level corresponding to >1012 parasites in an adult), mortality risk rises steeply. The major manifestations of severe falciparum malaria are shown in Table 116-2, and features indicating a poor prognosis are listed in Table 116-3. Cerebral Malaria Coma is a characteristic and ominous feature of falciparum malaria and, despite treatment, is associated with death rates of ~20% among adults and 15% among children. Cerebral malaria manifests as diffuse symmetric encephalopathy; focal neurologic signs are unusual. Although some passive resistance to head flexion may be detected, signs of meningeal irritation are lacking. The first symptoms of malaria are nonspecific; the lack of a sense of well-being, headache, fatigue, abdominal discomfort, and muscle aches followed by fever are all similar to the symptoms of a minor viral illness. In some instances, a prominence of headache, chest pain, abdominal pain, arthralgia, myalgia, or diarrhea may suggest another diagnosis. Although headache may be severe in malaria, there is no neck stiffness or photophobia resembling that in meningitis. The tendon reflexes are variable, and the plantar reflexes may be flexor or extensor; the abdominal and cremasteric reflexes are absent. Approximately 15% of patients have retinal hemorrhages; with pupillary dilatation and indirect ophthalmoscopy, this figure increases to 3040%. Convulsions, usually generalized and often repeated, occur in up to 50% of children with cerebral malaria. More covert seizure activity is also common, particularly among children, and may manifest as repetitive tonic-clonic eye movements or even hypersalivation. Approximately 10% of children surviving cerebral malaria have a persistent language deficit. The incidence of epilepsy is increased and the life expectancy decreased among these children. Hypoglycemia Hypoglycemia, an important and common complication of severe malaria, is associated with a poor prognosis and is particularly problematic in children and pregnant women. Hypoglycemia in malaria results from a failure of hepatic gluconeogenesis and an increase in the consumption of glucose by both host and, to a much lesser extent, the malaria parasites. To compound the situation, quinine and quinidine-drugs used for the treatment of severe chloroquine-resistant malaria-are powerful stimulants of pancreatic insulin secretion. The plasma concentrations of bicarbonate or lactate are the best biochemical prognosticators in severe malaria. Lactic acidosis is caused by the combination of anaerobic glycolysis in tissues where sequestered parasites interfere with microcirculatory flow, hypovolemia, lactate production by the parasites, and a failure of hepatic and renal lactate clearance. The pathogenesis of this variant of the adult respiratory distress syndrome is unclear. Noncardiogenic pulmonary edema can also develop in otherwise uncomplicated vivax malaria, where recovery is usual. Renal Impairment Renal impairment is common among adults with severe falciparum malaria but rare among children. The pathogenesis of renal failure is unclear but may be related to erythrocyte sequestration interfering with renal microcirculatory flow and metabolism. Clinically and pathologically, this syndrome manifests as acute tubular necrosis, although renal cortical necrosis never develops. Acute renal failure may occur simultaneously with other vital-organ dysfunction (in which case the mortality risk is high) or may progress as other disease manifestations resolve. In survivors, urine flow resumes in a median of 4 days, diagnosis of hypoglycemia is difficult: the usual physical signs (sweating, gooseflesh, tachycardia) are absent, and the neurologic impairment caused by hypoglycemia cannot be distinguished from that caused by malaria. In adults, coexisting renal impairment often compounds the acidosis; in children, ketoacidosis may also contribute. Acidotic breathing, sometimes called respiratory distress, is a sign of poor prognosis. Slight coagulation abnormalities are common in falciparum malaria, and mild thrombocytopenia is usual. Of patients with severe malaria, <5% have significant bleeding with evidence of disseminated intravascular coagulation. Hepatic dysfunction contributes to hypoglycemia, lactic acidosis,and impaired drug metabolism. Occasional patients with falciparum malaria may develop deep jaundice (with hemolytic, hepatitic, and cholestatic components) without evidence of other vital-organ dysfunction. Other Complications Septicemia may complicate severe malaria, particularly in children. Chest infections and catheter-induced urinary tract infections are common among patients who are unconscious for >3 days. The frequency of complications of severe falciparum malaria is summarized in Table 116-4. Anemia Convulsions Hypoglycemia Jaundice Renal failure Pulmonary edema + + + +++ +++ ++ ++ + +++ +++ +++ +++ +++ +++ +++ + - + Key: -, rare; +, infrequent; ++, frequent; +++, very frequent. In areas with unstable transmission of malaria, pregnant women are prone to severe infections and are particularly vulnerable to high-level parasitemia with anemia, hypoglycemia, and acute pulmonary edema.