Mestinon

General Information about Mestinon

Mestinon should be used with warning in sufferers with sure medical conditions, together with kidney or liver issues, asthma, epilepsy, and coronary heart disease. It could interact with different medications, corresponding to blood thinners and anticholinergics, so it is essential to inform your doctor about any medicines you are taking before beginning Mestinon.

Mestinon is often taken a number of occasions a day, at regular intervals, depending on the severity of the situation and particular person response. The dose is set by the prescribing doctor and may have to be adjusted over time to achieve one of the best results. It is necessary to observe the prescribed dosage and schedule to make sure the treatment's efficacy and stop potential side effects.

In conclusion, Mestinon is a valuable medicine for managing the symptoms of myasthenia gravis and different related circumstances. It works by bettering muscle energy and control, making it easier for patients to perform daily activities. However, like all medication, it is important to observe the prescribed dosage and be conscious of potential unwanted effects. Regular check-ups along with your physician might help monitor your response to Mestinon and adjust the therapy plan accordingly.

Mestinon is a cholinesterase inhibitor, which means it really works by stopping enzymes from breaking down acetylcholine, a chemical that carries indicators between nerves and muscular tissues. This drug helps to enhance muscle energy and management, thus alleviating the signs of myasthenia gravis. Mestinon is available in tablet, syrup, and injectable types, providing choices for patients with different wants.

Speaking of unwanted side effects, Mestinon may trigger some antagonistic reactions, and it's essential to be aware of them earlier than starting remedy. Common side effects could include belly cramping, nausea, diarrhea, extreme salivation, and sweating. These signs are sometimes transient and tend to enhance with continued use; nevertheless, if they persist or turn out to be severe, it is essential to inform your physician. Some patients may also expertise injection site reactions when using the injectable type of Mestinon.

The most typical use of Mestinon is within the treatment of myasthenia gravis. This situation is characterized by muscle weakness that worsens with physical exercise, and the severity of the signs can vary from person to person. The weakness usually impacts the eyes, face, throat, and limbs, making it troublesome to perform every day actions like chewing, swallowing, speaking, and even breathing. Mestinon has been shown to be efficient in relieving these symptoms, permitting sufferers to perform higher in their day-to-day lives.

Myasthenia gravis is a neuromuscular dysfunction that affects the voluntary muscular tissues, usually leading to weakness and fatigue. This situation happens when the communication between nerves and muscle tissue is disrupted, resulting in muscle weakness and difficulty with motion. One medicine that has been proven effective in managing the signs of myasthenia gravis is Mestinon, also referred to as Pyridostigmine.

Additionally, Mestinon can be used off-label for different circumstances such as Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome, a uncommon disorder that causes muscle weak point and fatigue. It may also be prescribed for sufferers with postoperative urinary retention, a situation by which the bladder can not totally empty after surgical procedure. In these instances, Mestinon helps to extend muscle strength and enhance bladder function.

Li Z muscle spasms yahoo answers mestinon 60 mg without prescription, Duan C, He J, et al: Mycophenolate mofetil therapy for children with steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome. Chandar J, Abitbol C, Montané B, et al: Angiotensin blockade as sole treatment for proteinuric kidney disease in children. Wang W, Xia Y, Mao J, et al: Treatment of tacrolimus or cyclosporine A in children with idiopathic nephrotic syndrome. Bagga A, Hari P, Moudgil A, et al: Mycophenolate mofetil and prednisolone therapy in children with steroid-dependent nephrotic syndrome. Mendizabal S, Zamora I, Berbel O, et al: Mycophenolate mofetil in steroid/cyclosporine-dependent/resistant nephrotic syndrome. Fujinaga S, Someya T, Watanabe T, et al: Cyclosporine versus mycophenolate mofetil for maintenance of remission of steroiddependent nephrotic syndrome after a single infusion of rituximab. Weiss R: Randomized double-blind placebo controlled, multicenter trial of levamisole for children with frequently relapsing/ steroid-dependent nephrotic syndrome. Basu B, Pandey R, Mondal N, et al: Efficacy and safety of mycophenolate mofetil vs. Ravani P, Ponticelli A, Siciliano C, et al: Rituximab is a safe and effective long-term treatment for children with steroid and calcineurin inhibitor-dependent idiopathic nephrotic syndrome. Ito S, Kamei K, Ogura M, et al: Survey of rituximab treatment for childhood-onset refractory nephrotic syndrome. Kamei K, Ito S, Nozu K, et al: Single dose of rituximab for refractory steroid-dependent nephrotic syndrome in children. Fujinaga S, Hirano D, Nishizaki N, et al: Single infusion of rituximab for persistent steroid-dependent minimal-change nephrotic syndrome after long-term cyclosporine. Magnasco A, Ravani P, Edefonti A, et al: Rituximab in children with resistant idiopathic nephrotic syndrome. Bagga A, Sinha A, Moudgil A: Rituximab in patients with the steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome. Rodriguez-Iturbe B, Batsford S: Pathogenesis of poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis a century after Clemens von Pirquet. Yoshizawa N, Yamakami K, Fujino M, et al: Nephritis-associated plasmin receptor and acute poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis: characterization of the antigen and associated immune response. Rodriguez-Iturbe B: Nephritis-associated streptococcal antigens: where are we now Raff A, Hebert T, Pullman J, et al: Crescentic post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis with nephrotic syndrome in the adult: is aggressive therapy warranted Suyama K, Kawasaki Y, Suzuki H: Girl with garland-pattern poststreptococcal acute glomerulonephritis presenting with renal failure and nephrotic syndrome. Zaffanello M, Cataldi L, Franchini M, et al: Evidence-based treatment limitations prevent any therapeutic recommendation for acute poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis in children. In Barratt J, Harris K, Topham P, editors: Oxford Desk Reference: Nephrology, Oxford, 2009, Oxford University Press, pp 214219. Mejia N, Santos F, Claverie-Martin F, et al: RenalTube group: Renal Tube: a network tool for clinical and genetic diagnosis of primary tubulopathies. Nesterova G, Gahl W: Nephropathic cystinosis: late complications of a multisystemic disease. Greco M, Brugnara M, Zaffanello M, et al: Long-term outcome of nephropathic cystinosis: a 20-year single-center experience. In Barratt J, Harris K, Topham P, editors: Oxford desk reference: nephrology, Oxford, England, 2009, Oxford University Press, pp 628631. Wühl E, Haffner D, Offner G, et al: European Study Group on Growth Hormone Treatment in Children with Nephropathic Cystinosis: Long-term treatment with growth hormone in short children with nephropathic cystinosis. DeFoor W, Minevich E, Jackson E, et al: Urinary metabolic evaluations in solitary and recurrent stone-forming children. Yamamoto M, Akatsu T, Nagase T, et al: Comparison of hypocalcemic hypercalciuria between patients with idiopathic hypoparathyroidism and those with gain-of-function mutations in the calcium-sensing receptor: is it possible to differentiate the two disorders Riveira-Munoz E, Chang Q, Godefroid N, et al: Belgian Network for Study of Gitelman Syndrome: Belgian network for study of Gitelman syndrome. Batlle D, Ghanekar H, Jain S, et al: Hereditary distal renal tubular acidosis: new understandings. In Barratt J, Harris K, Topham P, editors: Oxford desk reference: nephrology, Oxford, England, 2009, Oxford University Press, pp 208213. In Barratt J, Harris K, Topham P, editors: Oxford desk reference: nephrology, Oxford, England, 2009, Oxford University Press, pp 220224. Sáez-Torres C, Rodrigo D, Grases F, et al: Urinary excretion of calcium, magnesium, phosphate, citrate, oxalate, and uric acid by healthy schoolchildren using a 12-h collection protocol. Tekin A, Tekgul S, Atsu N, et al: A study of the etiology of idiopathic calcium urolithiasis in children: hypocitruria is the most important risk factor. Aydogdu O, Burgu B, Gucuk A, et al: Effectiveness of doxazosin in treatment of distal ureteral stones in children. Polito C, La Manna A, Nappi B, et al: Idiopathic hypercalciuria and hyperuricosuria: family prevalence of nephrolithiasis. Claverie-Martin F, Garcia-Nieto V, Loris C, et al: Renal Tube Group: Claudin 19 mutations and clinical phenotype in Spanish patients with familial hypomagnesemia with hypercalciuria and nephrocalcinosis. Font-Llitjós M, Jiménez-Vidal M, Bisceglia L, et al: New insights into cystinuria: 40 new mutations, genotype-phenotype correlation, and digenic inheritance causing partial phenotype. Takada Y, Kaneko N, Esumi H, et al: Human peroxisomal L-alanine: glyoxylate aminotransferase. Evolutionary loss of a mitochondrial targeting signal by point mutation of the initiation codon. In Barratt J, Harris K, Topham P, editors: Oxford desk reference: nephrology, Oxford, England, 2009, Oxford University Press, pp 632634.

Zaza G muscle relaxant you mean whiskey trusted mestinon 60 mg, Granata S, Sallustio F, et al: Pharmacogenomics: a new paradigm to personalize treatments in nephrology patients. Chatenoud L, Dugas B, Beaurain G, et al: Presence of preactivated T cells in hemodialyzed patients: their possible role in altered immunity. Thus, alterations in signal-feedback mechanisms and in production, transport, metabolism, elimination, and protein binding of hormones occur rather commonly in conditions affecting the kidney. The purpose of this chapter is to overview specific endocrine abnormalities that manifest as a consequence of kidney disease. If there is a concomitant inadequate secretion of insulin, this condition is manifested as abnormal glucose tolerance and if severe as diabetes mellitus. Later evidence suggests that fructose not only induces metabolic syndrome, hyperuricemia, and weight gain15 but also exerts direct adverse effects on renal tubular cells. Animal models of insulin deficiency suggest that the effect of insulin on protein turnover is mediated through the activation of the ubiquitin proteasome pathway. In a later evaluation of new users of oral hypoglycemic medication monotherapy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, higher risk of mortality was associated with glibenclamide, glipizide, and rosiglitazone than with metformin. A cross-sectional evaluation showed significantly higher (>38%) cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in rosiglitazone users,51 consistent with a systematic review of trials in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus that showed increased risk of myocardial infarction and a borderline increased risk of death from cardiovascular causes. Thus, a decline of kidney function is accompanied by a characteristic disturbance in thyroid physiology (Table 58. Medications that are able to suppress thyroid hormone metabolism include corticosteroids, amiodarone, propranolol, and lithium. Free and total thyroxine (T4) concentrations may be normal or slightly reduced, mainly as a result of impaired hormone binding to serum carrier proteins. Such finding differentiates the uremic patient from patients with other chronic illnesses. In addition, bioavailability and cell uptake of thyroid hormones may be partially blunted in uremia, leading to a state of thyroid resistance. In normal rat hepatocytes, treatment with serum from uremic patients reduced T4 uptake by 30%. In patients younger than 3 years, the head circumference should be routinely monitored as well. As a growth factor, prolactin influences hematopoiesis, angiogenesis, and blood clotting. Whether these effects were, at least partly, mediated by prolactin reduction is unknown. Although bromocriptine treatment has proved to decrease prolactin levels in uremic men and women,126 the previously mentioned symptoms do not fully disappear, suggesting that other factors may contribute in parallel. It is possible that prolactinemia may have previously underrecognized effects independent of its effects on the gonads. Aldosterone increases oxidative stress and promotes vascular inflammation143,144 and impairs vascular reactivity by limiting the bioavailability of nitric oxide. Ovarian dysfunction in women undergoing dialysis is characterized by the absence of cyclic gonadotropin and estradiol release, which results in the lack of progestational changes in the endometrium. Hypogonadism in women has been linked with sleep disorders, depression, urinary incontinence, and, in the long term, with osteoporosis, impaired cognitive function, and increased cardiovascular risk. Changes in lifestyle, such as smoking cessation, strength training, and aerobic exercises, may decrease depression, enhance body image, and have positive effects on sexuality. Sexual dysfunction in these patients should be thought of as a multifactorial problem that is affected by a variety of physiologic and psychological factors as well as comorbid conditions. In addition to a number of endocrine alterations described later, diabetes and vascular disease, for instance, can interfere with the ability of the male patient to achieve an erection and the female patient to achieve sexual arousal. Various psychological factors, such as depression, can significantly and adversely affect sexual function in both sexes. Chronic anovulation and lack of progesterone secretion in uremic women may be treated with oral progesterone. Low estradiol levels in amenorrheic women undergoing dialysis can lead to vaginal atrophy and dyspareunia; topical estrogen cream and vaginal lubricants may be helpful in these patients. Uremic women who are menstruating normally should be encouraged to use birth control. Estradiol hormonal replacement therapy was able to restore regular menses and improve sexual function in premenopausal estrogen-deficient women undergoing dialysis168 and to improve bone histomorphometry in animal models of uremia. In experimental animal models, endogenous estrogens have shown antifibrotic and anti-apoptotic effects in the kidney,175,176 and exogenous estradiol in ovariectomized rats attenuated glomerulosclerosis and tubulointerstitial fibrosis177 by protecting podocytes against injury through upregulation of estrogen receptor. However, clinical evidence in this regard is elusive, with evidence suggesting that both estrogen replacement therapy and oral contraceptives are associated with albuminuria, increased creatinine clearance, and loss of kidney function. Semen analysis typically shows a decreased volume of ejaculate, either low sperm count or complete azoospermia, and a low percentage of motility. In physiologic conditions, testosterone is an anabolic hormone that plays an important role in inducing skeletal muscle hypertrophy by promoting nitrogen retention, stimulating fractional muscle protein synthesis, inducing myoblast differentiation, and augmenting the efficiency of amino acid reuse by the skeletal muscle. However, testosterone may also have direct atheroprotective effects in the cardiovascular system. Thus, low testosterone could be considered a biomarker of chronic inflammatory disease. Alternative modes of administration, such as intramuscular injection, may ease compliance and bioavailability. In line with this thinking, a population-based study of men reported that impaired kidney function and low serum testosterone concentrations were additive (and independent) mortality risk factors.

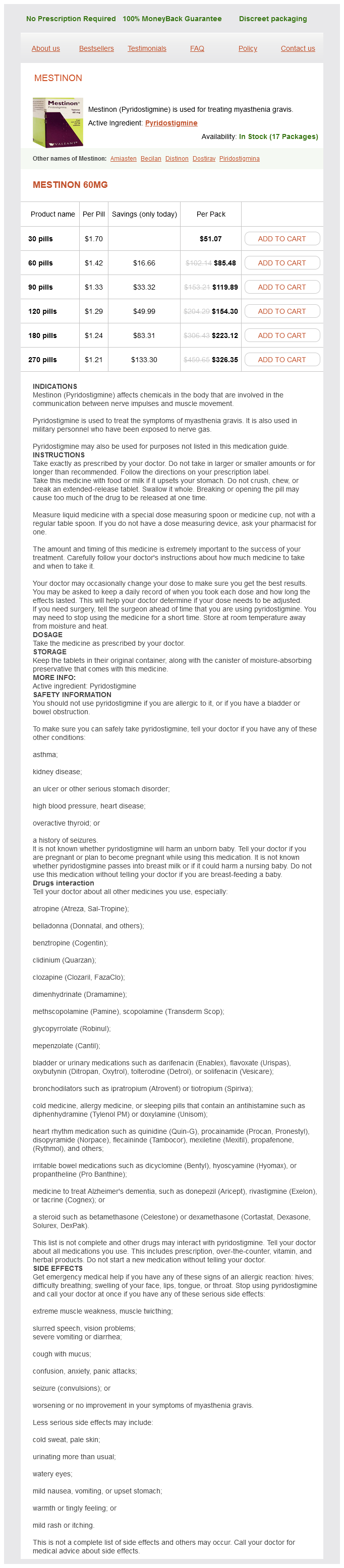

Mestinon Dosage and Price

Mestinon 60mg

- 30 pills - $51.07

- 60 pills - $85.48

- 90 pills - $119.89

- 120 pills - $154.30

- 180 pills - $223.12

- 270 pills - $326.35

Of the monogenic forms of hypertension with well-described molecular mechanisms muscle relaxant patch purchase mestinon 60 mg online, all have one thing in common: a defect in renal sodium handling. Mutations in two E3 ubiquitin ligase complex proteins (kelch-like 3 and cullin 3) were discovered later. The presumed mechanism is related to decreased channel ubiquitination and therefore persistent presence in the luminal membrane leading to the clinical phenotype of hypertension, hyperkalemia, and metabolic acidosis. This enzyme is responsible for the conversion of cortisol to the inactive cortisone in target epithelia, including the kidneys. As a result, excess cortisol is available to activate the mineralocorticoid receptor leading to a state of apparent mineralocorticoid excess (saltsensitive hypertension, hypokalemia, metabolic alkalosis) in the absence of aldosterone. Similarly, patients with congenital adrenal hyperplasia due to 11-hydroxylase or 17-hydroxylase deficiency have an excess production of 21-hydroxylated steroids such as deoxycorticosterone and corticosterone, which are potent activators of the mineralocorticoid receptor, thus also producing the syndrome of apparent mineralocorticoid excess in addition to the well-known sexual developmental abnormalities of the syndromes. Instead, urine sodium excretion varied as a function of circaseptan fluctuations (6 to 9 days in this case) in levels of aldosterone and cortisol/cortisone Moreover, total body sodium stores had even longer infradian variations (averaging several weeks). These observations have clinical implications for the use of urine sodium excretion to assess sodium intake because they suggest wide day-to-day variations that cannot60 be captured in a single 24-hour urine collection. However, this paradigm cannot explain the observation that acute sodium loading in humans and animals results in positive sodium balance without the expected water (weight) gain. Consequently, sodium may accumulate without water, most prominently in the skin,56 where negatively charged glycosaminoglycans bind sodium. The mechanisms explaining isosmotic sodium storage are under intense investigation. Mice and rats receiving a highsalt diet develop hypertonicity of the skin interstitium, which triggers a series of mechanisms to keep interstitial volume constant. Extensive nonepithelial effects include vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation, vascular extracellular matrix deposition, vascular remodeling and fibrosis, and increased oxidative stress leading to endothelial dysfunction and vasoconstriction. The vasodilatory effects are mediated by increased cyclic guanosine monophosphate, decreased norepinephrine release, and amplification of bradykinin effects. Many patients with hypertension are in a state of autonomic imbalance that encompasses increased sympathetic and decreased parasympathetic activity. For example, studies in humans have identified markers of sympathetic overactivity in normotensive individuals with a family history of hypertension. These findings can be interpreted within the paradigm that catecholamine-induced hypertension causes renal interstitial injury that associates with a saltsensitive phenotype even after sympathetic overactivity is no longer present. Renalase is a flavoprotein highly expressed in kidney and heart that metabolizes catecholamines and catecholaminelike substances to aminochrome. Chromogranin A knockout mice are hypertensive and have elevated catecholamine levels, both of which are normalized by administration of catestatin. Moreover, serum catestatin levels are decreased in patients with hypertension and their normotensive offspring, raising the possibility of a regulatory role in the development of hypertension. Activation of these same systems leads to a proinflammatory state related to increased reactive oxygen species, factors directly associated with endothelial dysfunction and vascular proliferation. Therefore, multiple mechanisms contribute to the development and maintenance of hypertension in obese individuals. Normotensive offspring of patients with hypertension have impaired endotheliumdependent vasodilation despite normal endothelium-independent responses, thus suggesting a genetic component to the development of endothelial dysfunction. They also inhibit renal sodium reabsorption through both direct and indirect effects. The inhibitory effects of natriuretic peptides on renin and aldosterone release mediate indirect effects. Other nonendothelium-derived factors may be of relevance to the genesis of hypertension via endothelium dysfunction. Much attention is given to uric acid, which can induce endothelial dysfunction and produce salt-sensitive hypertension through mechanisms that involve renal microvascular injury. Also of relevance is the possible role of high dietary fructose consumption in intracellular adenosine triphosphate depletion, increased oxidative stress, increased uric acid production, and endothelial dysfunction. In cross-sectional analyses, the lower the degree of forearm flow-mediated vasodilation, the greater the prevalence of hypertension. Cyclical pulsatile load is associated with fracture of elastin fibers and wall stiffening, and increased distending pressure demands recruitment of the less distensible collagen fibers, thus making vessels stiffer. Other studies corroborate these findings, but other studies also suggest a bidirectional relationship such that arterial stiffness is also a consequence of chronic hypertension. It is now apparent that the mechanism of damage of these organs, which are characterized by vasculatures with high flow and low impedance, is mediated by increased transmission of increased pulsatile pressure to the brain and renal parenchyma. This mismatch provokes wave reflection, thus protecting the tissue located distally to this reflection point from injury from the traveling pulse wave. In states of increased arterial stiffness, the stiffening of elastic arteries approximates the stiffness of muscular arteries, thus eliminating the protective impedance mismatch. Once impedances become "matched," there is less reflection and greater tissue injury, as supported by a growing body of clinical and experimental literature. In order to accomplish this, the clinician often needs multiple visits and judicious use of the clinical examination and a variety of laboratory and imaging tests. When searching for target-organ damage, one looks for symptoms to suggest a previous stroke or transient ischemic attack, previous or ongoing coronary ischemia, heart failure, peripheral arterial disease, or a past history of kidney disease or current symptoms such as hematuria or flank pain. Focus should be on the development of hypertension at a young age or clustering of endocrine (pheochromocytoma, multiple endocrine neoplasia, primary aldosteronism) or renal problems (polycystic kidney disease or any inherited form of kidney disease). The young patient with hypertension and a family history of hypertension poses a particular challenge and should be evaluated in detail. For example, patients with reactive airways disease (asthma) probably should not receive -blockers, patients with prostatic hyperplasia may benefit from a regimen that includes an -blocker, and patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder or anxiety may benefit from a central sympatholytic. It is also important to recognize that it is during the history that the clinician has the opportunity to explore issues related to lifestyle, cultural beliefs, and patient preferences that will be essential in designing an effective treatment plan. It is important to define eating and physical activity patterns and, when problems are identified, to determine if the patient is willing and/or able to modify them.